|

So I promise I will get back to Evolution for the layman Part 2. Soon enough, but I thought I would get back to talking about the project over here in Panama. So a huge part of evolution and natural selection is looking at survival. So you know we released lots of lizards onto islands across Lake Gatun in Panama. Or if you didn't you do now. So we successfully finished the transplants around mid September, 70 lizards per island, 6 islands. A far cry from the original target of 100 each on 12 islands. But that's fieldwork, you always seem, in hindsight, to have originally aimed for the moon. But what happens now? So we released all these lizards to islands, big deal. Well next step is to see how many are still surviving after the initial transplant and how many are still surviving through to December. Our initial worry was that none would have survived, a bit of a stupid worry to have really as our entire project was based around their survival? But yes, no guarantees. So the initial pilot study fortunately went exceptionally well. We managed to see several surviving adults, including a breeding pair (caught in the act) and even some juveniles that were born on the island! So that left us hopeful, and hence the reason for the Dr Ian Malcolm quote. If you don't know the quote, then you need to give yourself a stern talking to. 3 weeks on, full scale recaptures are taking place and the numbers are slowly racking up. On one of the islands we managed to find the minimum we need on the first day. So for island A: any more lizards that we find are a bonus. But we still need to hit the target minimum, some will be very hard work due to the huge complexity of the islands. Island B: is like a giant birds nest, with branches everywhere! So why do we need to recapture these lizards? Well essentially we want to know which of the initial individuals we released form the mainland survived and which ones didn't. When you know that, you can look into what traits, or characteristics are common in the survivors. Do all the survivors have longer tails, or shorter legs? If there is a correlation then you can hypothesize that this could be the trait that selection is acting upon. I am obviously over simplifying this, but hopefully you get the picture. Assuming selection favours short legs, you would assume that the vast majourity of surviving lizards will be the ones from the initial population that had the shortest legs. You have to be able to say why shorter legs, as you'll remember from my Evolution for the layman. Selection acts on phenotype and phenotypes are influenced by the environment. That is something we aim to do next year, to characterize the habitat so we know why a trait or phenotype is being favoured by selection. But right now we want to know which individuals are surviving. Notable Sightings: West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus) American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) Crab Eater Fox (Cerdocyon thous) Red Tailed Boa Constrictor (Boa constrictor constrictor) I was once, rightfully, criticized for writing a too self indulgent blog. So I feel I should, at times, take a tangent off to talk about actual science, before promptly returning to talking about myself. But I am actually talking about the science of my PhD, so I guess I am in a way indirectly talking about myself?

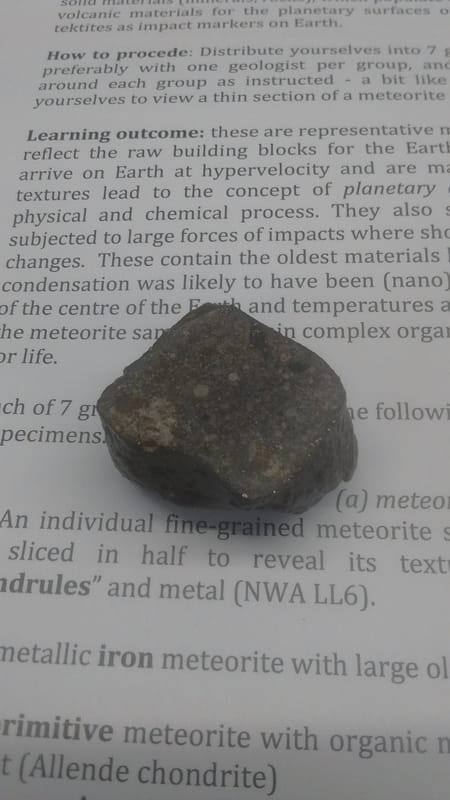

So the whole premise of my current PhD is looking at contemporary evolution. Evolution that happens over a short time period. "But Dan, Evolution takes millions of years!!" I hear most of you cry or "Evolution isn't real!" a alarming number of people might say, fortunately I don't know any of the latter and may they return to whatever bridge/rock they crawled out from under. To the former, those who like Darwin assumed that evolution is a lumbering leviathan taking a geological epoch to move from A to B, you are wrong. Plain and simple, wrong. I know, I spoke blaspheme about the great Darwin. He was many great things but greatness is not a constant beam of light, it flickers and wains from time to time and for the timescale of evolution it waned somewhat. So if evolution is not a great lumbering beast, then what is it? Well to leap to Darwin's defense (and undermine my own argument) on some scales it is exceedingly slow. The evolution of theropod dinosaurs to what we now know as birds took millions of millions of years, but the change from the infamous Velociraptor to the humble woodpecker is quite a complex change, relatively speaking. Evolution of course doesn't have to be as complicated as the change of Dinosaurs to birds. Evolution is essentially just a genetic change, or a change that can be inherited. The simplest definition of evolution is "a change in allele frequency" (non biologists can gloss over that, or google it). It can be a genetic change that causes a slight change in a species's colour or a slight difference in leg size. It doesn't have to be a huge change, just one that can be inherited. And that, that can be seen over short time periods! A few hundred years, a hundred years, a few decades and even just a few years! If you have the right pressures and environment you will see evolutionary change in a short time period. Each year new cases of rapid evolution crop up. A well known example for anyone who has done Biology at school in the UK is the Peppered Moth which promptly evolved in response to the industrial revolution, producing more and more black winged individuals which were more camouflaged on the dark pollution covered trees, and back again when the air became cleaner in recent decades. There are many other examples across the globe, the Guppies of Trinidad for instance were the anvil on which most modern experimental evolutionary studies were forged, and of course the numerous studies of the Anole lizards in the Caribbean, which readily adapt their limb size to cope with a change in arboreal environment. So ultimately you want to know, can we see evolution over the course of my project? Potentially! There is definitely a possibility that we see an evolutionary response to the increased temperature of the islands we are moving the lizards too. But there are many other aspects we can focus on. So evolution doesn't just happen on a whim, there are driving forces that cause the change and evolution of species. These driving forces are natural selection (made infamous in the "Origin of Species") and sexual selection. Now I won't be touching on sexual selection for the most part so feel free to do your own ground work on that one, but I will be talking about Natural Selection a significant amount. Natural selection is the driving force of evolution, evolution happens to a population but selection happens to the individual. An individual is "selected" to survive depending on how well suited it is to the environment. If it does survive it, potentially, gets to reproduce. if it gets to reproduce then it gets to pass on its genetic material. Say there is a population of 1 million mice and selection favours 500,000 of them. Then the genetic material of 500,000 mice is transferred to the next population, so even though selection acts on the individual scale this up and it can make a huge difference on the next generation, and the next and the next and so forth, eventually if you see genetic change then you have evolution (in a nutshell). But how does selection work, what do I mean "selection favours"? That is a story for another day... Part 2 coming up! The bulk of the work for the last few weeks has been collecting and processing as many lizards as we can catch. Over 400 in fact which may sound a lot but we actually wanted nearly 700-800 by this point with a total of 1200. But it seems we are going to fall very short of that mark, especially as our collaborators from Georgia Southern are leaving in a few days. The reason behind our struggles? Well imagine having to look for a 4cm brown lizard (see image below) in an almost infinite Jungle, not only that but it spends its time on brown branches under leaves. So you can imagine that it is pretty difficult to see them at the best of times. But it also seems they are in much lower numbers than they were a few years ago when my supervisor conducted a reconnaissance of the area. Population cycles like this are perfectly normal, predator prey interactions, food availability and temperature all play a part in population declines and increases. Its not just a species going to extinction. See classic examples such as Lynx and Hare population dynamics, which was always the quintessential case study during my undergraduate Zoology degree.

But back to the point, it seems like the population (from an anecdotal perspective) is lower than it was a year or two ago. Which means we are not getting the number of lizards we wanted when we go out to catch them. Instead of 100 in a day (Which is what we expected) its closer to 60-80 over 2 days. Apart from the one day where we caught 80 in a day. But there in lies the other problem. The weather. A very small lizard is hugely dependent on the weather. Lizards maintain their body temperature by utilizing the temperature of the environment. In places like the UK and Europe Lizards need to devote a lot of time basking in the sun or laying on warm rocks to heat their body. In the tropics this is mostly unnecessary due to the night time temperatures often being above 24 degrees. But even a few degrees change can alter everything (the whole premise of my PhD). When the stars aligned and we got the right mix of temperature, humidity and sun exposure we were able to get 80 lizards in one day. But for the last two sessions we were not in the gods favour. Too much rain got us the first time and the last two days before our collaborators leave were stinking hot causing many of the lizards to be in hiding or very hyper (hotter the lizard is the more energy it has, to a certain degree. Too much heat = DEATH). This hyperactivity makes them very hard to catch if they are out in these hotter days. So basically we are not getting as many lizards as we want and we are running out of time because all the lizards need to be taken to the lab for two days to get physical data from them. Meaning the project has to be scaled back from 100 Lizards on 12 islands to 100 Lizards on 6 islands. Not ideal, but that's unfortunately how it goes with fieldwork. I should have followed my own advice. Assume nothing, expect everything. But best laid plans and all that. Time to make the best of the situation! Species Sightings: Derby's Woolly Opossum (Caluromys derbianus) Northern Tamandua (Tamandua mexicana) Great Tinamou (Tinamus major) So sloth is certainly not one of the deadly sins exhibited this week! So what else could my biblical referenced title be about?

This week the project was joined by Dr Christian Cox and 2 masters students from his lab (www.coxevolab.org), who came here to help the establishment of the Panama project. With their arrival the project began in earnest! After assuming the lizards we were after (Anolis apletophallus) were hugely abundant we erroneously assumed that we could catch 100 in a day relatively easily. Now we know that they are abundant, BUT they are also hugely cryptic (camouflaged) and very small so its very difficult to see them especially when you factor in the dynamic and complex jungle ecosystem. So we are now catching about 60-80 over two days and it's quite a lot of work. So that was a kick in the teeth a little, not as bad as day one where it took us two hours to find 3. I was f-ing and blinding that day, assuming my PhD was sunk already. Fortunately you begin to develop a "search image", which is kind of like your brain filtering out background visual noise and making it easy to see the specific shape or pattern of the thing you are looking for. This makes it easier to spot them and our numbers began to climb up and hopefully will continue to do so. On day one of lizard collection we also managed to see something many people who spend months in the jungle do not... A jaguar! No, I joke. We were not that lucky. But we did see a sloth! Ok, not fast moving but its a greyish/brown/ greenish animal in a greyish/brownish/greenish forest and it normally spends 99% of its time in the canopy. Most of the last few days have been spent ferociously hunting for lizards and then meticulously measuring them, doing temperature trials on then and marking them ready for release. Not too complicated right? Well we spent nearly 12 hours in the lab one day and I was there for an extra 3 to finish up, getting home around midnight.There are a fair few teething problems in the first week as this is a brand new project. So hopefully there won't be too many days like that. But I have definitely taken one thing away from these few days, don't underestimate teething problems! But we have managed to get one island populated with lizards! Another notable thing to mention was the night hike, a nice foray into the jungle to search for nocturnal beasts. Which was a success! We saw hundreds of frogs including one of my new favorites the Gladiator Tree frog and one animal I have really wanted to see for years; the Kinkajou! He was waiting for us right next to the car when we returned. Pretty good side dish of glamour to our long hours of monotony right? Notable Animal Sightings: Three Toed Sloth (Bradypus variegatus) Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus capucinus) Spectacled Caiman (Caiman crocodilus) Gladiator Tree Frog (Hypsiboas rosenbergi) Gaudy Leaf Frog (Agalychnis callidryas) Kinkajou (Potos flavus) Geoffrey's Tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi)  Me with all 221 data loggers ready to be taken out to the forest! Me with all 221 data loggers ready to be taken out to the forest! For a bit of context to my blog from Panama please see my Research page to understand what I am doing. The first week of my 5 months in Panama is now over. I could tell you about the gliz and glamour, all the high points and the cheesy movie perfect phrases. But this is not an over edited picture perfect Instagram account. I did however enjoy my first week, but I am sure many of you will ask why, after reading this. Let me begin with the key words for week one. "Optimum Temperature Models" what are these you ask? They are devices to record temperature that are created and distributed in such as way as to match the habitat and therefore relative temperatures that your study organism would be exposed to. E.g. if you were studying mole rats you would create an OTM that would have the same temperature absorbing properties of a molerat (don't ask me how to do that) and place it in an underground burrow at the same depth a molerat burrow would be. That is a very inaccurate and over simplified analogy, but what the hell, run with it. So anyway, my PhD is looking at the evolutionary change of lizards in response to climate change (or climate warming) so obviously temperature is a big deal. This is the part of science many people don't communicate and many people who want to be scientists don't realize. Some of the work is tedious and dull (if you go into Microbiology or soil science it's all tedious and dull, in my opinion....) but it needs to be done. You can't just swan over to Panama throw buckets of lizards at islands and watch the data roll in. You need to do the nitty gritty. So my first week was basically, individually plugging 221 temperature recorders into my laptop, programming them to record every hour. Then coating them in a waterproof plastic. Then peeling them off the desk because the the plastic had stuck them to the table. Then giving them a second coat. Then cutting off the excess plastic to neaten them up. Oh and finally we had to stick them to bits of wood to make it easier to attach them to trees. Then it was of we went (We is myself and Dr Michael Logan, who is my friend and 3rd PhD supervisor) to our 12 survey islands. These islands are hotter than the mainland so give us the ability to mimic climate change when we move lizards from the mainland to said islands. But how much hotter, well we need to know exactly across the course of the year. So before we do anything, we need environmental data. Otherwise how can we prove that these hotter islands are the cause for evolutionary change? Because they might actually not be hotter, or maybe its only the hottest island that causes a change but we wouldn't know this if we did compare temperature data to evolutionary data. I digress, back to the fieldwork. Blasting around the Panama Canal on a small metal boat and doing Seal Team like landings on our sample islands kept the boyish part of me happy but we also had to distribute 17 OTM's across each island to mimic how lizards would distribute themselves when they are released to the islands over the next few weeks. So a pretty busy first week, not as glamorous as I am sure I would like to tell you, but this ladies and gentlemen is Science. Often glamour is a side dish, not the main course! But, it is a damn fine side dish! Notable Animal Sightings: Howler Monkeys - Heard rather than seen, every time it rains they howl as loud as they can. Poison Dart Frog - Dendrobates auratus  “Ecological Armageddon” – The effect of a Hydroelectric Dam on Biodiversity in Thailand. “Ecological Armageddon” – The effect of a Hydroelectric Dam on Biodiversity in Thailand. Conservation biologists, as the world sees them, are people running around the globe trying to save everything from the clutches of extinction. For some animals, their doom seems to be rapidly approaching, with vastly low numbers and impossible odds. For others, it seems the downward spiral is just beginning. But one creature, I fear may become rarer than anything else, rarer than the kakapo of New Zealand, rarer than the black- crested gibbon of SE Asia. The rare “creature” I am speaking of is optimism and it is a creature that could become even rarer. OK, so I’m probably being melodramatic. But go look around, see the latest stories from Mongabay for example. Another mine? palm oil story? An ecologically dead river? Depressing reading, right? I myself have worked in beautiful places only to see the vast amount of damage humans have done. Thailand for example, where the construction of a hydro-electric dam has caused huge declines in biodiversity. “Ecological Armageddon” was a phrase used after an assessment of the area. To hell with it, then right? After the disastrous events of early November surely it is time for conservationist to give up the ghost? How do we stay optimistic about now? So, let’s just pack in conservation and leave the world to ruin. Let the lack of action be the tinder on which the natural world burns. Absolutely not! Optimistic, yet realistic. That’s how I feel your mindset should be when working in conservation. I mentioned all the doom and gloom stories, we as conservationists acknowledge this. “conservation biology has arguably become the most depressing of the sciences” – James Sheppard in the Mongabay Article that inspired this piece. So yes, it is depressing but who doesn’t love a good underdog story? *insert inspirational Rocky quote of your choice here*, Snatching victory from the jaws of defeat? It has a nice ring to it does it not? It’s the train of thought you must have. You might be the most cynical human being on earth, but if you are working with a species on the edge of extinction, you have no option but to make yourself optimistic. You may have some nocturnal existential crises as you lay awake into the night, you may even curl up in a ball, biting a flannel as you sob in the shower. The latter is a bit extreme but it has probably happened in conservation somewhere. I have certainly doubted my work and the work of the project I have been involved in. To give you a real-world example, I recently returned from working on the Mountain Chicken Frog Project. The frog itself was decimated by the Chytrid Fungus that caused one of the fastest species declines in history with >85% population decline in less than 2 years. So, the numbers you are working with are tiny (less than 150 confirmed in the wild) so all the threats are made stronger because you can lose everything with one disastrous event, such as a tropical storm which happen frequently in the frog’s homeland of Dominica (West Indies). While working on the project I would frequently be asked; “How many frogs are left on Dominica?”, obviously a very important question. The response would often be met with “is that all?” even by non-scientists. If you told a scientist, it was often a four-letter word I probably can’t repeat here. So back to “optimistic, yet realistic”. How can I be optimistic when faced with such low numbers and almost endless threats? How could I not place a shotgun in my mouth with a toe on the trigger? Because I feel there is still hope. There were numerous positive signs while I was out there; successful breeding, potential disease resistance and healthy animals. But as I said before you have to be realistic about these things because the species is still on a razors edge, a nudge in either direction and it falls off the face of the earth forever. If these endangered species start falling into the abyss, so will conservationists. When deep in the doldrums, I wrote to David Attenborough, to ask how he stays positive. “I could not let a grandchild of mine say; grandfather you knew this was coming and you did nothing”. Obviously not true in his case, but a good lesson for us all. It does seem in today’s world that there is a never-ending torrent of stories of how it’s all for nothing. But to end on a high, do google some success stories, stories such as the US Regulations on Ivory and the plight of the Californian Condor. Truth be told, in my opinion all is not lost so I choose to be optimistic. Now, now more than ever we need to be optimistic. Well my first term as a PhD student is over. It was a little different to most PhDs but I have done a lot and learned a lot and I now have a PhD Thesis title, sort of (work starts in January). I will be looking at the evolutionary ecology of reptiles after they have been moved to a new ecosystem. The ecosystem being on the Panama canal so yes, guess where my field work will be based? I will be moving from University College London to Queen Mary University and I will be working alongside The Institute of Zoology, The Smithsonian and Harvard University. So yeah, this programme has really worked out well for me!

Over the last few months I have: Had several free tours of London Zoo Had several behind the scenes tours of the Natural History Museum Held a 3.4 billion year old asteroid Gone fossil hunting in Norfolk Observed pollution rates in central London Flown a drone in a nightclub Planned for a space weather disaster Planned for a volcanic eruption Had a behind the scenes tour of Kew Gardens Enjoyed my 20% at the Natural History Museum Taken advantage of the copius free alcohol and food suppied by various univerities Enjoyed a free hotel at Brunel University and targeted birds with a directional microphone at Queen Mary University. So, I am actually getting paid to do science! What the hell, right?? Yes it has actually happened. I am now a fully fledged PhD student. The interviews are over, no more PhD interviews!!!!!! I am now a PhD Researcher on the London NERC Doctoral Trainining Programme (NERC for anyone who is interested is the National Environmental Research Council, or the people who should have made RSS Boaty McBoatface... but then didnt). I won't bog you down with too many details about the programme but the first 3 months have me bouncing round most of the univeristies in London (not dirty imperial though) as well as the academic institutions (Kew Gardens, Natural History Museum and London Zoo) to learn the vast inner workings of environmental science. From earthquakes and space weather to plants and evolution. Now I go to spend my first real wage packet....

Watch this space! Well I said in my last post did I not? That I did not think we would get to number 100 before I left. Well ladies and gentlemen, I was WRONG!! On my final night out in the field with an entourage of 6 Operation Wallacea students/staff I was able to find 3 more new captures. "But wait, surely that only brings you to 97 Dan?" Yes, dear reader you are correct! However on the way home I heard a very large male calling in a brand new area, so I knew this one would be number 100, so off I went to find him! There he was sat in a Dasheen plantation ready to be scooped up! As I was very close to the Operation Wallacea base of operations on Dominica I thought I would do a little additional outreach/education while I was there. So I introduced them to number 100. Got to say, I was in such a good mood on my final days in Dominica due to this fantastic final night of fieldwork! There were plenty of ups and plenty of downs while I was out in Dominica but it was a great experience! Thanks to all who contributed to the project, joined me in the field etc etc! I don't to the over emotional teary goodbyes you see far to often in blogs these days, but thanks everyone!

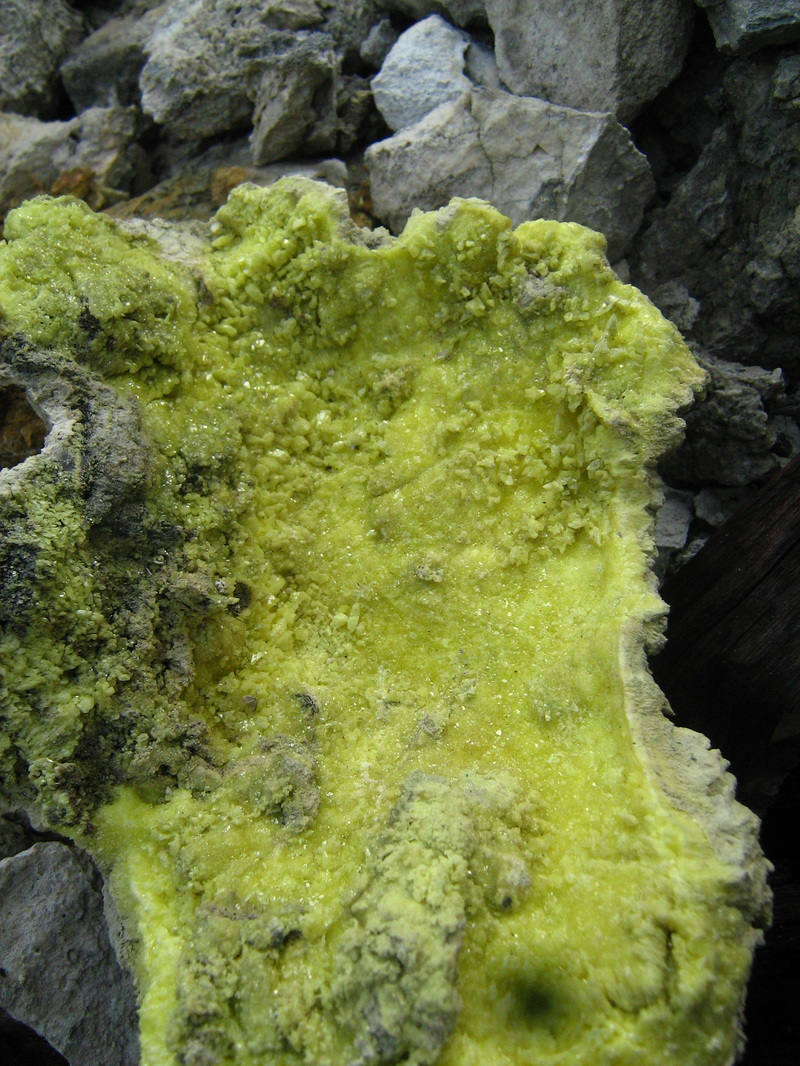

I fly home in two days to begin my next adventure, up the academic ivory tower with my PhD! Took a field trip with my friend the Volcanologist to the Soufriere Sulphur Springs a huge deposit of sulphur deposits from the the many volcanoes on the island. Not really much more to say on the matter, I did have my sling on so make sure not to tell my doctor I was hiking.. Pictures will say it all.

We also conducted a frog survey that evening which was a great night! Managed to find two brand new frogs! A HUGE female filled with eggs (#95 now called Maria after one of our volunteers) and a male right next to her (#96 AKA Dre) so they were looking for some romance.... until we broke them up. It was only temporary he was calling within 5 minutes of letting him go so he didn't give a toss it seems. Getting very close to 100 recorded individuals, not bad to say we were at 64 when I arrived. Am I the cause of this explosion of recorded frogs, well yes. Yes I am. Dominica, you are welcome. With only 2.5 weeks left its looking unlikely I will see the 100th frog but what the hell I did my part! |

Archives

October 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed